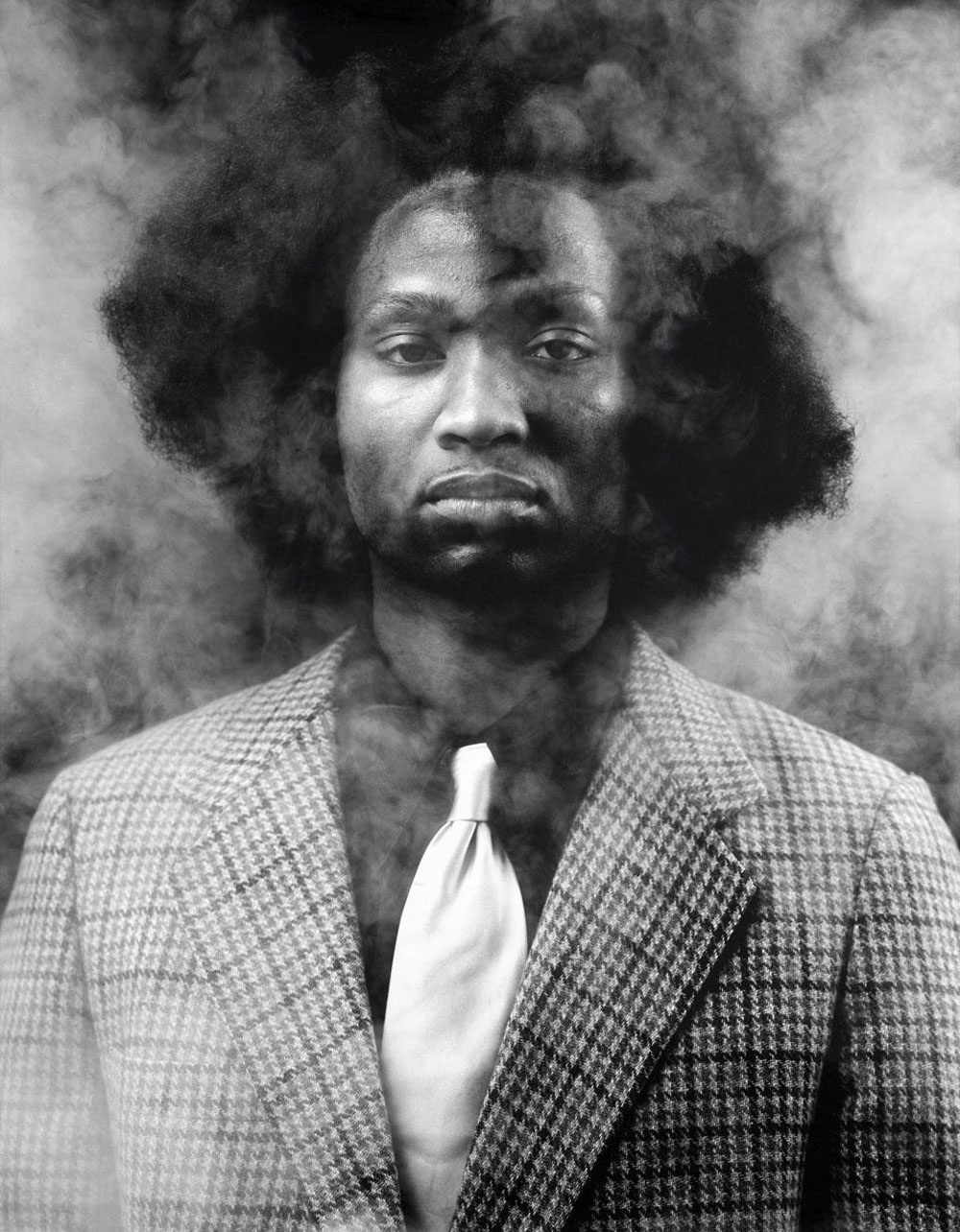

Demonstrating a great fascination and embrace of African-American culture from throughout history, Johnson creates works that display interweaving references, drawing connections and hierarchies between important African-American figures, events, texts and other historically-significant materials. Such artifactual relationships establish a rich and systematic collection of memories and snapshots that reflects a complex and vivid language for discussing this African intellectual history. In his installation work, Rashid Johnson demonstrates an obsessive craft of intimate detail, creating complex pieces with many small objects and other subtle visual imagery that all pay homage to something from the afrocentric past. By making these historical connections, Johnson draws conclusions on the single story of the African-American experience through the last few centuries and how it has encountered many recurring triumphs and struggles.

Originally focused on portrait photography, Rashid Johnson has always sought to tell the story of the African-American. Since breaking into installation art and experimenting with new materials such as black wax soap and shea butter (which both reference African culture), his work has become ever-more complex. With such intricate pieces it is important to note how conceptual accessibility plays a role in the power of the art. Beginning with his photographed portraits, Johnson has had a keen eye on emphasizing the distinct loss in translation for African-American culture to his caucasian audience (which racially dominates the art world today). With the installation pieces Johnson brings out a rich and detailed story that his audience cannot fully comprehend, an experience that strengthens his concept yet inhibits his audience from fully engaging with the work.

Such a presentational dilemma is clear in the piece How Ya Like Me Now (2010, Persian rug, gold embroidery and shea butter). Unless the viewer can recognize that the design stitched into the rug is the logo of hip-hop group Public Enemy, and that many of the group's performers are also members of the Nation of Islam movement, the connection between the pop culture icon and religious motif would not come across as fluid as Johnson had hoped.

Despite this break in the chain of dialogue between artist and audience, the art demonstrates a unique testament to everything historically African-American. For Johnson's work to be successful and penetrating, his audience must have the same obsessive knowledge of African intellectual history as that of the artist, because once a viewer can identify each reference and historical nod, he can then lay out the pieces and solve the puzzle that Johnson lays out in his "Post-Black" art. With this in mind we must ask whether it is the audience that isn't getting the message across, rather than placing the blame on the artist.

Originally focused on portrait photography, Rashid Johnson has always sought to tell the story of the African-American. Since breaking into installation art and experimenting with new materials such as black wax soap and shea butter (which both reference African culture), his work has become ever-more complex. With such intricate pieces it is important to note how conceptual accessibility plays a role in the power of the art. Beginning with his photographed portraits, Johnson has had a keen eye on emphasizing the distinct loss in translation for African-American culture to his caucasian audience (which racially dominates the art world today). With the installation pieces Johnson brings out a rich and detailed story that his audience cannot fully comprehend, an experience that strengthens his concept yet inhibits his audience from fully engaging with the work.

Despite this break in the chain of dialogue between artist and audience, the art demonstrates a unique testament to everything historically African-American. For Johnson's work to be successful and penetrating, his audience must have the same obsessive knowledge of African intellectual history as that of the artist, because once a viewer can identify each reference and historical nod, he can then lay out the pieces and solve the puzzle that Johnson lays out in his "Post-Black" art. With this in mind we must ask whether it is the audience that isn't getting the message across, rather than placing the blame on the artist.

No comments:

Post a Comment